RESUMEN

Entre las complicaciones posoperatorias, es frecuente la microfiltración cuando se realizan restauraciones directas con resina en el sector posterior, sobre todo en la parte profunda de las cajas proximales. Objetivo: Evaluar por medio de un estéreo microscopio si resinas nano híbridas Bulk Fill presentan menor grado de microfiltración marginal en cavidades clase II que resinas nano híbridas convencionales. Materiales y métodos: Cavidades estandarizadas clase II de Black de 30 premolares extraídos por indicación ortodóntica fueron restauradas aleatoriamente en dos grupos (n= 15). El primer grupo fue restaurado con resina nano híbrida Tetric EvoCeram® (Ivoclar) con incrementos de 2mm y el segundo grupo con resina nano híbridas Bulk Fill (ivoclar) con incrementos de 4 mm. Todas las muestras fueron sometidas a termociclado durante 5000 ciclos y posteriormente fueron sumergidas en azul de metileno durante 24 horas. Finalmente, se realizó un corte sagital de manera uniforme y se evaluó la profundidad de la microfiltración marginal en la base de la caja proximal por medio de un estéreo microscopio y el análisis de dos observadores ciegos. Resultados: Los dos grupos presentaron microfiltración marginal, en distintos grados. Conclusión: aunque las cavidades restauradas con resina nano híbridas Bulk Fill presentaron valores menores, la prueba de Mann Whitney dio como resultado que las diferencias existentes no son estadísticamente significativas (p = 0,181).

Palabras clave: Adaptación Marginal, Resinas Compuestas, Materiales Dentales, Fracaso de la Restauración, Filtración Dental.

ABSTRACT

Among postoperative complications, microfiltration is frequent when direct restorations with resin are performed in the posterior sector, especially in the deep part of the proximal boxes. Objective: To evaluate by means of a stereo microscope if Bulk Fill nano-hybrid resins have a lower degree of marginal microfiltration in class II cavities than conventional nano-hybrid resins. Materials and methods: Standardized Black class II cavities of 30 premolars extracted by orthodontic indication were randomly restored in two groups (n = 15). The first group was restored with Tetric EvoCeram® nano hybrid resin (Ivoclar) with 2mm increments and the second group with Bulk Fill (ivoclar) nano hybrid resin with 4mm increments. All samples were subjected to thermocycling for 5000 cycles and subsequently immersed in methylene blue for 24 hours. Finally, a sagittal section was performed uniformly and the depth of marginal microfiltration at the base of the proximal box was evaluated by means of a stereo microscope and the analysis of two blind observers. Results: The two groups presented marginal microfiltration, in varying degrees. Conclusion: Although the cavities restored with Bulk Fill nano-hybrid resin presented lower values, the Mann Whitney test resulted in the existing differences not being statistically significant (p = 0.181).

Keywords: Marginal adaptation, Composite Resins, Dental Materials; Dental restauration failure, Dental leakage.

RESUMO

Entre as complicações pós-operatórias, a microfiltração é frequente quando restaurações diretas com resina são realizadas no setor posterior, principalmente na parte profunda das caixas proximais. Objetivo: Avaliar, por meio de um estereomicroscópio, se as resinas nano-híbridas Bulk Fill apresentam um menor grau de microfiltração marginal nas cavidades da classe II do que as resinas nano-híbridas convencionais. Materiais e métodos: Cavidades padronizadas de classe II de Black de 30 pré-molares extraídos por indicação ortodôntica foram restauradas aleatoriamente em dois grupos (n = 15). O primeiro grupo foi restaurado com resina nano-híbrida Tetric EvoCeram® (Ivoclar) com incrementos de 2 mm e o segundo grupo com resina nano-híbrida Bulk Fill (ivoclar) com incrementos de 4 mm. Todas as amostras foram submetidas a termociclagem por 5000 ciclos e subsequentemente imersas em azul de metileno por 24 horas. Finalmente, uma seção sagital foi realizada de maneira uniforme e a profundidade da microfiltração marginal na base da caixa proximal foi avaliada por meio de um estereomicroscópio e a análise de dois observadores cegos. Resultados: Os dois grupos apresentaram microfiltração marginal, em graus variados. Conclusão: Embora as cavidades restauradas com a resina nano-híbrida Bulk Fill apresentem valores mais baixos, o teste de Mann Whitney determinou que as diferenças existentes não fossem estatisticamente significativas (p = 0,181).

Palavras-chave: Adaptação marginal, resinas compostas, materiais dentários, falha na restauração, filtragem dentária

INTRODUCTION

For almost 100 years for the restoration of posterior teeth, the material used was amalgam. However, the concepts of aesthetics and toxicity of mercury have caused innovated with other restorative materials1; The composite resins have booming, beginning the era of adhesion.This fact has been one of the greatest contributions to dental practice, because they are highly aesthetic materials and have better adhesive properties to dental tissue compared to amalgam, less microfiltration is obtained, the remaining dental structure is maintained and a remaining dental structure is produced. Good transmission of the masticatory forces through the adhesive interface of the tooth. However, among the disadvantages, polymerization contraction may occur at the tooth-restoration interface and give rise to marginal microfiltration2.

According to Ramírez & cols. (2009), composite resin-based materials are a clinical option for restoration, being aesthetic and presenting adhesion to the dental structure and its durability is proven. The main goals of the restorations are to seal the dentin exposed to the oral environment, prevent recurrence of tooth decay and preserve the health of the dental piece3.

Microfiltration is a problem that is frequently found in restorations in the posterior sector; especially in the deep part of the proximal boxes of class II restorations. In this type, the adaptation in the gingival margin can occur due to a polymerization contraction, which increases the risk of microfiltration and post-operative sensitivity1.

In order to minimize this contraction, modifications have been made to the chemical formula of the material, such as the addition of low shrinkage monomers or an increase in the volume of fillers, using new types of the same. In this way, new formulas of composite resins are obtained (nano hybrids, micro hybrids, nano fillers, ormoceramics, etc.)2,3. These investigations gave rise to dental materials, such as Bulk Fill resin, which breaks with traditional methods of application, since it allows to place blocks of up to 4 millimeters, achieving a faster application and less clinical work time. Its polymerization only needs 10 seconds, thanks to its light-sensitive accelerators and filters, which allow a deeper cure4.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the degree of marginal microfiltration observed in premolars that underwent aging by thermocycling and dye penetration1.

Methods

The research was developed after the approval of the Ethics and Research subcommittee of the Central University of Ecuador. In vitro comparative study. The sample was composed of 30 human premolars extracted for orthodontic reasons, with informed consent. After the extraction it was verified that they are healthy, free of cavities, restorations and any lesions. They were washed and debris removed with ultrasound. The samples were kept until the experiment in saline solution, which was changed every week, at a temperature of 37 ± 5°C.

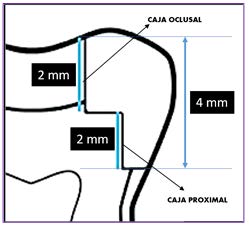

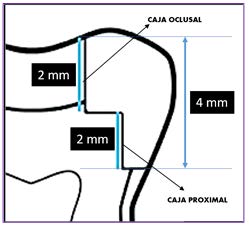

For the test, standardized class II cavities were carried out with the following measures: the occlusal box was formed with 4mm in the buco-lingual direction, 4mm in the distal mesio direction and 2mm in depth. Proximal box: from the pulp floor 2mm (4mm from the surface cape edge) and 2mm in the mesio-distal direction (Figure 1). In each sample the measurements of the cavity were verified, the preparations should not have sharp edges or angles and the enamel edge was slightly rounded; Samples that did not meet.

Figure 1. Cavity delimitation

Previously to the placement of the 2 restorative materials; The 30 cavities were washed with water spray and dried with sterile cotton swabs. The etching and adhesion protocol in all samples was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. 37% phosphoric acid (N-Etch® - Ivoclar) was used for dentin and enamel etching for 15 seconds, then rinsed with water spray for 30 seconds and dried slightly with air, avoiding excessive drying. Next, a thick layer of Tetric® N-Bond (Ivoclar) was applied to the enamel and dentin surfaces, using an applicator gently rubbed the dentin material for 10 seconds, the excess material and solvent they removed by means of an air jet and the adhesive spread so that it completely covers the enamel and dentin without accumulation inside the cavity. The photo curing, performed perpendicularly 1 mm from the occlusal face was performed for 10 seconds with an Elipar® lamp (3M), with a light intensity of ± 800 mW / cm2.

The restoration material was placed according to the manufacturer's instructions by randomly placing the material in 2 groups (n = 15). For group A, restorations with nano-hybrid resin (Tetric EvoCeram®) were carried out using the incremental technique, with 2 increments of 2mm; Group B samples were restored with Bulk Fill nano-hybrid resin (Tetric EvoCeram® Bulk Fill), which was placed using the incremental mono technique, with a single increment of 4 mm. The photo curing was performed after each resin increase by placing the lamp perpendicularly 1 mm from the occlusal face for 20 seconds with an Elipar® lamp (3M), with a light intensity of ± 800 mW / cm2.

Subsequently both groups were waterproofed with a layer of enamel (for Rodher nails) and subjected to 5000 cycles of thermocycling at temperatures between 5 °, 37 ° and 55 °. The samples remained 20 seconds at each of the temperatures, plus 5 seconds of transport between one temperature and another. Once the thermocycling was finished, they were immersed in a solution of methylene blue for 24 hours. Afterwards, the water jet was washed for 1 minute to thereby remove the excess dye.

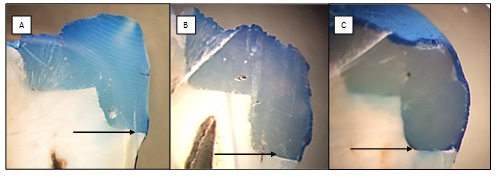

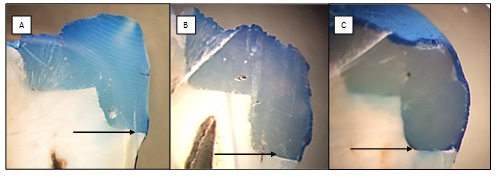

Continuing with the procedure, the samples were sectioned longitudinally with a diamond disk under constant irrigation. An observational analysis was carried out using a stereo microscope to determine the degree of existing marginal microfiltration. The values that were taken into account for the evaluation were the following2.5:

- Null: if the indicator does not penetrate the tissue (0 mm). Rating 0.

- Slight: if the indicator penetrates minimally into the examined wall, less than half of the wall (1mm). Rating 1.

- Moderate: if the staining is up to half of the examined wall (2mm) Assessment 2.

- Severe: if the staining rate exceeds half of the examined wall (more than 2 mm). Rating 3.

Figure 2. Microfiltration scales: A: mild; B: moderate; C: severe

Results

Two blind observers performed the observation, their data was stored in Excel, concordance between the observers was demonstrated by the kappa test. The values were symmetric (Table 1).

| GRUPOS |

KAPPA |

| A |

0,820 |

| B |

0,902 |

Cuadro 1. Kappa Concordance Test between observers.

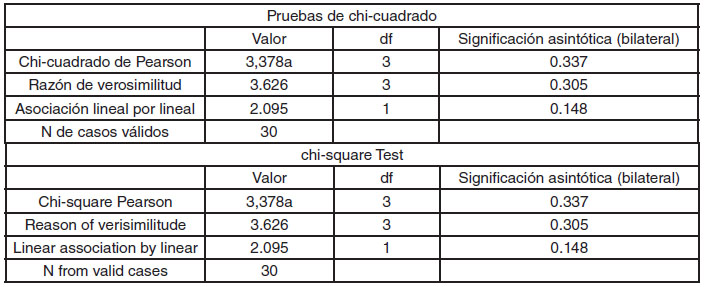

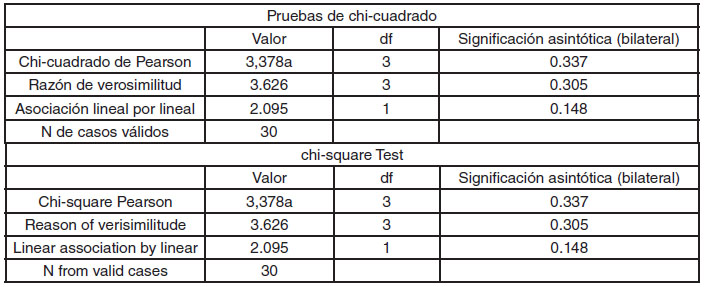

Categorical data were analyzed by means of the X2 test in the SPSS 24 (IBM) software, with a level of significance of 95%, which resulted in no statistically significant differences between the two groups examined (p => 0.05), determining that marginal filtration does not depend on the type of material studied, so the null hypothesis of the investigation is accepted (Table 2).

Cuadro 2. Comparison between groups by X2, p => o.o5

Discussion

hrough the present study, it was intended to determine if bulk fill resins, thanks to their properties, manage to reduce filtration in the proximal boxes of class II cavities. Based on the methodology used, it was observed that there is no significant difference in the marginal filtration between the materials used Tetric EvoCeram® and Tetric EvoCeram® Bulk Fill (Ivoclar).

In 2013, Uehara et al., Conducted a comparative study of marginal adaptation in which they used three types of resins: conventional Filtek Z350 (3M), Bulk Fill Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivovlar) nano-hybrid resin and Sonic Fill (Kerr)7. The samples were subjected to 100 cycles of thermocycling and as a result the three groups presented marginal maladaptation; concordant with the exposed data in which both experimental groups present microfiltration.However, the authors find that Bulk Fill resin was the one with the greatest marginal adaptation compared to the two remaining groups. This result differs from those obtained in the present study, where similar marginal microfiltration is observed for the Bulk Fill nano hybrid resin. The type of cavity and the reduced sample size have an impact on the comparison of the results.

Campos et al. In 2014 they carried out a comparative study between Bulk Fill resins of different commercial brands that are in the market. Once the samples were restored, they were subjected to occlusal loads and thermocycling cycles. As a result, it was evidenced that in all the groups the presence of marginal microfiltration is observed, as well as that seen in this study10.

Lois et al. In 2003, they conducted a study to evaluate marginal microfiltration in class II cavities, which were restored with Surefil® resin (Dentsply), applying different sealing techniques both incremental and incremental mono. It was obtained as results that none of the techniques completely eliminates marginal microfiltration1. In the exposed methodology, two types of increment (2 and 4 mm) have been used, according to the characteristics of each material and not as a research subject, so it could not be specified if the resin increase in each case determines or not a greater marginal filtration.

Similarly, Furness et al. (2014), conducted a comparative study between the techniques of incremental and incremental mono resin placement, to examine internal marginal adaptation. As a result, it was observed that there were no significant differences between the two, since a complete marginal adaptation was not achieved12.

Dominguez et al. (2015) performed a new comparative analysis, in this case, of the degree of marginal sealing in class II cavities between the Tetric N-Ceram® Bulk Fill resin and the Tetric N-Ceram® resin. The procedure consisted of subjecting dental pieces to 250 cycles of thermocycling. The result was that conventional Tetric N-Ceram resins had a better marginal seal than Tetric N-Ceram Bulk Fill resin. However, the results achieved in our study contradict those achieved by Dominguez et al. This can be explained by the number of thermocycling cycles, since 5000 cycles were performed in the present study, which is equivalent to 6 months of aging of the dental pieces5.

Bulk Fill resins are used by the incremental mono technique or layered up to 4 mm. This technique was studied by Pacheco et al., Rosas et al., Hilton et al. and Gallo et al.; which compared the incremental technique with the incremental mono technique of Bulk Fill resins. In each case, the samples were subjected to thermocycling cycles, resulting in no statistically significant difference in marginal adaptation. These investigations corroborate what was found in our study: in the two groups that were investigated (15 premolars restored in each one) a presence of marginal micro filtration was found8,9,13,14.

Once the results obtained in this investigation have been analyzed, it can be considered that, although Bulk Fill nano-hybrid resin reduces working time, it does not differ in the degree of filtration in the proximal box in class II cavities, according to the method used in the experiment . It is necessary to take into consideration that this technique shows advantages and disadvantages, so it is recommended to conduct more studies that evaluate together other factors that directly affect the degree of maladaptation and marginal microfiltration.

Conclusions

According to the method used in the present investigation, it can be concluded that there are no significant differences in the degree of marginal filtration in class II cavities restored with Tetric EvoCeram® and Tetric EvoCeram® Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) resins.

Bibliografía

- Zeballos L., Pérez Álvaro. Materiales Dentales De Restauración. Revista de Actualización Clínica. 2013; (30): 1498-1504.

- Lois M., Paz R., & Pazos S. Estudio in vitro de microfiltración en obturaciones de clase II de resina compuesta condensable. Av. Odontoestomatol. 2004; 20 (2): 85-94.

- Ramírez R. A., Setién V., Orellana N., & García C. Microfiltración en cavidades clase II restauradas con resinas compuestas de baja contracción. Acta Odontológica Venezolana. 2009; 47(1): 131-139

- Mahn E. Cambiando el paradigma de la aplicación de composites: Tetric Evoceram® Bulk Fill. Ivoclar Vivadent - Special Edition, 1-24.

- Domínguez Burich R. Análisis comparativo in vitro del grado de sellado marginal de restauraciones de resina compuesta realizadas con un material monoincremental (TETRIC N-CERAM BULK FILL), Y UNO CONVENCIONAL TETRIC N-CERAM)". Tesis. Santiago De Chile: Universidad De Chile, Facultad De Odontología; 2014

- Nocchi, E. Odontología restauradora. Salud y estética. 2ª ed., Buenos Aires: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2008. p.2-5.

- Uehara N., Ruiz A., Velasco J. Adaptación Marginal De Las Resinas Bulk Fill. Marginal Adaptation Of Bulk Fill Resin. RODYB. 2013; 2(3); 1-10

- Rosas B., Soto V., Ruiz P., Estabilidad marginal de una resina condensable versus resina monoincremental activada sónicamente en restauraciones clase II: Estudio in vitro. Av. Odontoestomatol. 2016; 32(1): 45-53

- Pachecho C., Gehrkue A., Aragonés P. Evaluación de la adaptación interna de resinas compuestas: Técnica incremental versus bulk-fill con activación sónica. Av. Odontoestomatol. 2015; 31(5): 313-321.

- Alves, E., Ardu, S., Lefever, D., & Jasse, F. F. ScienceDirect Marginal adaptation of class II cavities restored with bulk-fill composites. J Dent. 2014; 42(5): 575-581

- Lally U. Restoring class II cavities with composite resin, utilising the bulk filling technique. J Ir Dental Ass 2014:60(2):74-76

- Furness A, Tadros MY, Looney SW, Rueggeberg FA. Effect of bulk/incremental fill on internal gap formation of bulk-fill composites. J Dent 2014; 42(4): 439-449.

- Hilton T. Schwartz RS, Ferrancane JL. Microleakage of four Class II resin composite insertion techniques at intraoral temperature. Quintessence Int, 1997; 28(2); 135-144.

- Gallo JR, Bates ML, Burgess JO. Microleakage and adaptation of class II packable resin-based composites using incremental or bulk filling techniques. Am J Dent 2000;13(2): 205-208.

- Alshali RZ, Salim NA, Satterthwaite JD, Silikas N. Post-irradiation hardness development, chemical softening, and thermal stability of bulk-fill and conventional resin-composites. J Dent 2015;43 (2):209-18.

- Heintze SD, Monreal D, Peschke A. Marginal Quality of Class II Composite Restorations Placed in Bulk Compared to an Incremental Technique: Evaluation with SEM and Stereomicroscope. J Adhes Dent 2015;17(2):147-54.

- El-Damanhoury H, Platt J. Polymerization shrinkage stress kinetics and related properties of bulk-fill resin composites. Oper Dent. 2014;39(4):374-82.

- Nagi SM, Moharam LM, Zaazou MH. Effect of resin thickness, and curing time on the micro-hardness of bulk-fill resin composites. J Clin Exp Dent. 2015;7(5):e600-4.

- Orłowski M, Tarczydło B, Chałas R. Evaluation of Marginal Integrity of Four Bulk-Fill Dental Composite Materials: In Vitro Study. Sci World J 2015;2015:1-8.

- Benetti A, Havndrup-Pedersen C, Honoré D, Pedersen M, Pallesen U. Bulk-Fill Resin Composites: Polymerization Contraction, Depth of Cure, and Gap Formation. Oper Dent 2015;40(2):190- 200.

|

|

| |

| |

| |

Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual

CC BY-NC-SA

Esta licencia permite a otros entremezclar, ajustar y construir a partir de su obra con fines no comerciales, siempre y cuando le reconozcan la autorÍa y sus nuevas creaciones estÉn bajo una licencia con los mismos tÉrminos.